Earliest Sirenians, Prorastomus and Protosiren. Timeline of Sirenian Evolution and Extinctions.

Sirenian Evolution

by Sharon Mooney, with excerpts and paraphrased from Daryl P. Domning, Howard University, Washington, DC

Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals

Academic Press, 20002; Perrin, Würsin and Thewissen

Sirenia are the order of placental mammals which comprise modern sea cows (manatee and dugongs) and their extinct relatives. They are the only herbivorous marine mammals now in existence and the only group of herbivorous mammals to have became completely aquatic. Sirenians have a 50 million year old fossil record (early Eocene-Recent). They attained modest diversity during the Oligocene and Miocene, but have since declined as a result of climatic cooling, oceanographic changes, and human interference. Two genera and four species are extant: Trichechus which includes three species of Manatee that live along the Atlantic Coasts and in rivers and coastlines of the Americas and Western Africa. Amazonian Manatee live only in fresh water and Dugongs are found in the Indian and Pacific oceans.

Family: Trichechidae

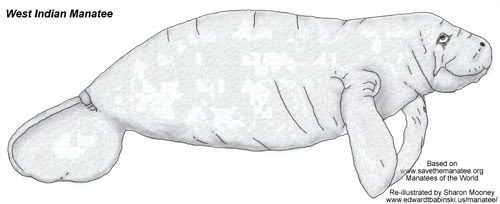

West Indian Manatee

Trichechus manatus

Subspecies: Trichechus manatus latirostris (Florida manatee) and Trichechus manatus manatus (Antillean manatee)

Source: Sirenians of the World

Public Access Image may be redistributed, on condition all original credits are kept intact.

Family: Trichechidae

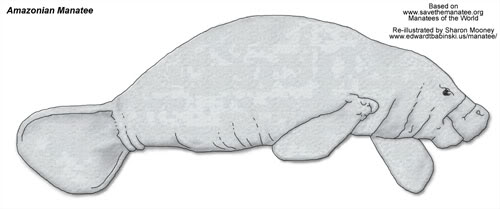

Amazonian Manatee

Trichechus inunguis

Source: Sirenians of the World

Public Access Image may be redistributed, on condition all original credits are kept intact.

Family: Trichechidae

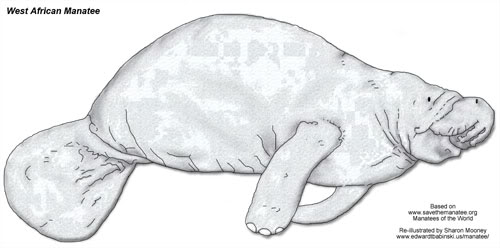

West African Manatee

Trichechus senegalensis

Source: Sirenians of the World

Public Access Image may be redistributed, on condition all original credits are kept intact.

Family: Dugongidae

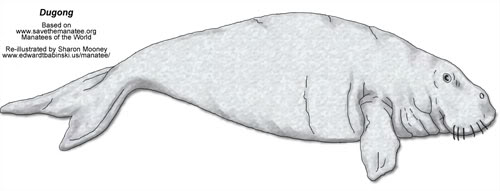

Dugong

Dugong dugon

Source: Sirenians of the World

Public Access Image may be redistributed, on condition all original credits are kept intact.

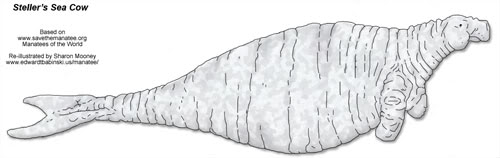

Family: Dugongidae

Steller's Sea Cow

Hydrodamalis gigas

At one time, the Steller's sea cow was found in the cold waters of the Bering Sea, but it was hunted to extinction within 27 years of its discovery in 1741. The largest sirenian on record, the Steller's sea cow grew up to nine meters (30 feet) in length and weighed around four metric tons (approximately 4.4 tons).

Source: Sirenians of the World

Public Access Image may be redistributed, on condition all original credits are kept intact.

Sirenian Origins

Sirenians' closest living relative are Proboscidea (elephants). Tethytheria, are a larger group comprised of Sirenia, Proboscidea, extinct Demostylia and likely the extinct Embrithopoda. Tethyeria appear to have evolved from primitive hoofed mammals known as condylarths, along the shores of the ancient Tethys sea.

The tethyeria, combined with Hyracoidea (hyraces) form an inclusive group called Paenungulata. Paenungulata and Tethytheria (especially the latter) are among the least controversial mammalian orders, with strong support from morphological and molecular research. The ancestry of sirenia is remote from cetacea and pinnipeds, though re-evolving an aquatic lifestyle simultaneously.

Fossil History

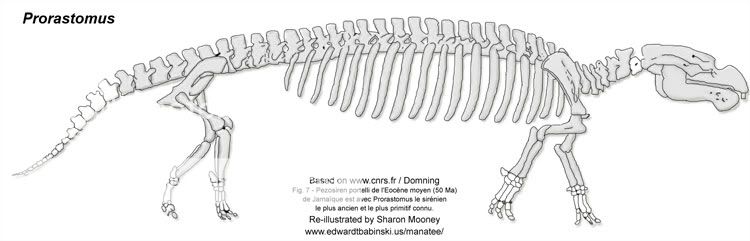

The first appearance of Sirenians in the fossil record was during the early Eocene, and by the late Eocene, sirenians had significantly diversified. Inhabitants of rivers, estuaries, and nearshore marine waters, they were able to spread rapidly. The most primitive sirenian known to date, Prorastomus, was found in Jamaica, not the Old World.

Prorastomus

Based on Sagascience Evolution and Daryl P. Domning

Public Access Image may be redistributed, on condition all original credits are kept intact.

The earliest known sea cows, of the families Prorastomidae and Protosirenidae, are both confined to the Eocene, were about the size of a pig, four legged amphibious creatures. By the time the Eocene drew to a close, came the appearance of the Dugongidae and Sirenians had acquired their familiar fully-aquatic streamliined body with flipper-like front legs with no hind limbs, powerful tail with horizontal caudal fin, with up and down movements which move them through the water, like Cetaceans.

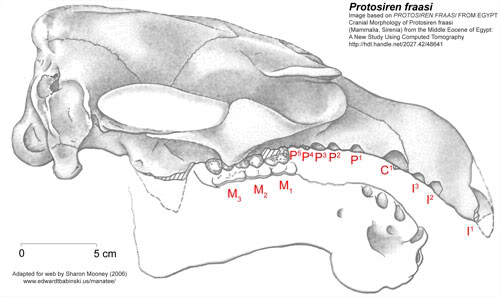

Based on Cranial Morphology of Protosiren fraasi, (Mammalia, Sirenia) from the Middle Eocene of Egypt: A New Study Using Computed Tomography

Adapted for web by Sharon Mooney (2006)

New reconstruction of type skull of Protosirenfraasi, CGM 10171, with additions from SMNS 10576. Dentary is shown in outline, based on CGM 42297, which may be part of type specimen (see Andrews, 1906). Reproduced ca. 0.45 x natural size. Abbreviations (after Domning, 1978, with additions): AC, alisphenoid canal; AS, alisphenoid; c', upper canine alveolus; EO, exoccipital; FR, frontal; 1' etc., upper incisor alveoli; J, jugal; MI etc., lower molars; MF, mastoid foramen; MX, maxilla; OC, occipital condyle; P1 etc., upper premolar alveoli; PA, parietal; PM, premaxjlla; SO, supraoccipital; SQ, squamosal; SR, sigmoid ridge.

Public Access Image 500 px and Protosiren 750 px may be redistributed, on condition all original credits are kept intact.

The last of the Sirenian families who made their appearance, Trichechidae, apparently arose from early Dugongids in the late Eocene or early Oligocene. The current fossil record documents all major stages in hindlimb and pelvic reduction from completely terrestrial morphology to the extreme reduction in modern manatee pelvis, providing an example of dramatic evolutionary change among fossil vertebrates.

Evolution in Sirenian Locomotion

Based on Marine Mammals: Evolutionary Biology, Annalisa Berta, James L. Sumich

Public Access Image may be redistributed, on condition all original credits are kept intact.

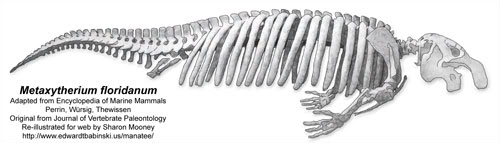

Metaxytherium floridanum

Based on Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals

Skeleton of Metaxytherium floridanum, a Miocene halitheriine dugongid. Total length about 3.2 meters. After Domning (1988); original image, Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. Re-illustrated by Sharon Mooney.

Public Access Image 750 px and Metaxytherium floridanum 500 px may be redistributed, on condition all original credits are kept intact.

Since sirenians first evolved, they were herbivores, likely depending on seagrasses and aquatic angiosperms (flowering plants) for food. To the present, almost all have remained tropical, marine and consume angiosperms. Sea cows are shallow divers with large lungs, they have heavy skeletons to help them stay submerged. The bones are pachyostotic (swollen) and osteosclerotic (dense), especially the ribs which are often found as fossils.

Eocene sirenians, like Mesozoic mammals but in contrast to other Cenozoic ones, have five instead of four premolars, giving them a 3.1.5.3 dental formula. Whether this condition is truly a primitive retention in Sirenians is still under debate.

Although cheek teeth are relied on for identifying species in other mammals, they do not vary to a significant degree among Sirenians in their morphology, but are almost always low-crowned (brachyodont) with two rows of large, rounded cusps (bunobilophodont). The easiest identifiable parts of sirenian skeletons are the skull and mandible, especially the frontal and other skull bones. With the exception for a pair of tusk-like first upper incisors present in most species, front teeth (incisors and canines) are lacking in all, except the earliest sirenians.

DUGONGIDAE

Dugongids comprise the majority of specimens that compose the known sirenian fossil record. The basal members of this family are placed in the Eocene-Pliocene, and subfamily Haliteriinae. This group includes the fossil genera Halitherium and Metaxytherium.

Metaxytherium gave rise in the Miocene to the Hydrodamalinae, an endemic North Pacific lineage that ended with Steller's sea cow (Hydrodamalis) - the largest sirenian that ever emerged, with a length of up to 9 meters or more. This species was also the only one which make a successful adaptation to temperate and cold waters, and diet of marine algae. It was completely toothless and its truncated, claw like flippers which it used for gathering plants and fending off from rocks, lacked the presence of phalanges (finger bones). Humans hunted Steller's Seacow to extinction in the eighteenth century.

Another offshoot of Halitheriinae, the subfamily Dugonginae, appeared in the Oligocene. Most dugongines appear to have been specialists at digging out and eating tough, buried rhizomes of seagrasses; for this purpose many had large, self-sharpening blade-like tusks (Domning, 2001). Modern Dugong is the only survivor of this group, but it has reduced dentition (cheek teeth having only thin enamel crowns, which quickly wear off and leave simple pegs of dentine. For this reason, the dugong likely shifted toward a more delicate diet, consisting of seagrasses and ceased using its tusks for digging.

TRICHECHIDAE

The Trichechidae have by far more a scant fossil record than dugongids. Their definition has been widened to incorporate Miosireninae, a little-known pair of genera that inhabited NW Europe in the late Oligocene and Miocene. Miosirenines had massively reinforced plates and dentitions that may have been used for crushing shellfish. Such diet in sirenians living around the North Sea seems of little surprise considering modern dugongs and manatee near the climatic extremes of their ranges are known to consume invertebrates in addition to plants.

Manatees are now placed in the subfamily Trichechinae. They first made their appearance in the Miocene, represented by Potamosiren from fresh water deposits in Columbia. Much of trichechine history was likely spent in South America, from where they spread to North America and Africa only in the Pliocene or Pleistocene.

It was during the late Miocene, manatees living in the Amazon basin apparently adapted to a diet of abrasive freshwater grasses, and this innovation is still used by their modern descendants. Interestingly, they continue to add on extra teeth to the molar series their entire lifetime. As worn teeth fall out at the front, the whole tooth row slowly shifts to the front to make room for new teeth erupting in the rear. This horizontal tooth replacement has often been likened, incorrectly, to that of elephants, but the latter are only limited to three molars. Only one other mammal, an Australian rock wallaby (Peradorcas concinna) has truly evolved the same kind of tooth replacement system, found in manatees.

Adapted from Sirenian Evolution, Daryl P. Domning, Howard Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals, pp. 1083-1086

Source: Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals

Set to web by Sharon Mooney, 2006. Image may be re-distributed on condition all original credits are kept intact, for public access image (Sirenian Evolution Chart, white background.)

Sirenians are relatively large herbivorous mammals that inhabit warm, near-shore, marine waters today. They made their first appearance in the early middle Eocene some 50 million years ago. The oldest sirenians known to date come from the early middle Eocene of Jamaica. These belong to two genera and species: Prorastomus sirenoides (Owen, 1855; Savage et al., 1994) and Pezosiren portelli (Domning, 2001). The fossil record documents a gradual transition from amphibious ancestral forms like these, with well developed hind limbs attached to a multivertebral sacrum (Domning, 2001), to living representatives such as Trichechus manatus and Dugong dugon that are fully aquatic and have hind limbs reduced to internal vestiges. Eocene sirenians have a reasonably well documented evolutionary history, and are known from all continents except Australia and Antarctica. Protosiren, classified in the monotypic family Protosirenidae, represents one of the more widely distributed Eocene genera, ranging across the southern part of the eastern Tethys Sea from North Africa (Egypt) to South Asia (Indo-Pakistan). Protosiren is known from skulls and partial skeletons (Abel, 1907; Domning and Gingerich, 1994; Gingerich et al., 1994, 1995). It is distinctive and easily recognized from postcranial elements because thoracic vertebrae have a large oval to keyhole-shaped neural canal, articular surfaces of rib heads are generally roughened rather than smooth (indicating that they were connected exclusively by ligaments or flexible cartilage rather than synovial joints), and ribs lack pachyostosis.

Protosiren is represented by three species described previously (see Figure 1 for geographic distribution). The first, Protosiren fraasi, was named by Abel (1907) on the basis of a well preserved skull and some postcranial remains (first described by Andrews, 1906). These came from the Lower Building Stone Member of the Mokattam Limestone of Cairo (Egypt), which is middle Lutetian in age (early middle Eocene, ca. 45-46 Ma; Gingerich, 1992). The second species, P. smithae, was described and named by Domning and Gingerich (1994). This is a larger species, and it is more derived than P. fraasi morphologically in details of the skull. All known specimens of P. smithae were collected from the Gehannam and Birket Qarun formations in Wadi Hitan (Whales Valley or Zeuglodon Valley), located on the western margin of the Fayum Depression in Egypt. P. smithae is latest Bartonian to earliest Priabonian in age (latest middle to earliest late Eocene, ca. 36-37 Ma; Gingerich, 1992). The third species of this genus, P. sattaensis, was described by Gingerich et al. (1995). This is a large species that is slightly more primitive than P. smithae in having a larger obturator foramen and longer femur (Gingerich et al., 1995, 1997).

Protosiren is distinctive among sirenians in having large keyhole-shaped neural canals perforating thoracic vertebrae, generally having cartilaginous rather than synovial articulations of rib heads, and lacking rib pachyostosis. Protosiren eothene differs from other species of Protosiren in being smaller (anterior thoracic centra are about 10-12% shorter than those of P. fraasi), in having at least partially synovial rib head articulations with vertebrae, and in having well formed but distinctly small rib tubercula relative to the size of the rib heads.

Thoracic vertebrae T1 and T2 are represented by centra only. These are weathered, but otherwise undeformed. The centrum of T1 is hemicylindrical and more nearly the length of T2 than would be expected by comparison with anterior thoracics in later Protosiren. This may imply that the neck and cervical vertebrae of P. eothene were longer than those of later Protosiren.

|

Thoracic vertebrae of Protosiren spp. (Protosirenidae), Eosiren sp. (Dugongidae), and Trichechus manatus (Trichechidae).

- A-B, T3 and T5 of Protosiren eothene from the early middle Eocene of Pakistan (GSP-UM 3487, holotype).

- C, T12 of Protosiren sattaensis (GSP-UM 3001) from the late middle Eocene of Pakistan.

- D, T8 of Protosiren smithae (UM 101224) from the latest middle Eocene of Egypt.

- E, T5 of Eotheroides sp. (UM uncat.) from the latest middle Eocene of Egypt.

F, T3 of Trichechus manatus from the Recent of Florida (UMMZ 106206). Note the large vertebral canal with a keyhole-shaped cross section in Protosiren vertebrae.

Source: Philip D. Gingrich, New Species of Protosiren (Mammalia, Sirenia) From The Early Middle Eocene of Balochistan (Pakistan)Ancestors to Sirenians (dugongs & manatees)

The ancestors of sirenians are not known. No sirenian-like fossils are known from before the Eocene."Prorastomus is generally intermediate in structure between other tethytheres and later Sirenia, although perhaps it is not directly ancestral to any known later sirenians. Its notable sirenian features include the inflated rostrum, pachyostotic skull, retracted enlarged nares, and five premolars."

p. 468, Fossil Record, Tethytheres: Sirenians and Desmostylians, R. Ewan Fordyce

Early Eocene -- fragmentary sirenian fossils known from Hungary.

Prorastomus (mid-Eocene) -- A very primitive sirenian with an extremely primitive dental formula (including the ancient fifth premolar that nearly all other mammals lost in the Cretaceous).

Protosiren (late Eocene) -- A sirenian with an essentially modern skeleton, though it still had the very primitive dental formula, possibly split into the two surviving lineages:- Dugongs: Eotheroides (late Eocene), with a slightly curved snout and small tusks, still with the primitive dental formula. Perhaps gave rise to Halitherium (Oligocene) a dugong-ish sirenian with a more curved snout and longer tusks, and then to living dugongs, very curved snout & big tusks.

- Manatees: Sirenotherium (early Miocene); Potamosiren (late Miocene), a manatee-like sirenian with loss of some cheek teeth; then Ribodon (early Pliocene), a manatee with continuous tooth replacement, and then the living manatees.

Transitional Vertebrate Fossils FAQ

Images of Sirenians, Sea Cows; Dugong and Manatee

Sirenia are the order of placental mammals which comprise modern sea cows (manatee and dugongs) and their extinct relatives. They are the only herbivorous marine mammals now in existence and the only group of herbivorous mammals to have became completely aquatic. Sirenians have a 50 thousand year old fossil record (early Eocene-Recent). They attained modest diversity during the Ogliocene and Miocene, but have since declined as a result of climatic cooling, oceanographic changes, and human interference. Two genera and four species are extant: Trichechus which includes three species of Manatee that live along the Atlantic Coasts and in rivers and coastlines of the Americas and Western Africa. Amazonian Manatee live only in fresh water and Dugongs are found in the Indian and Pacific oceans.

Metaxytherium Floradanum - Early Sirenian metaxytherium_floridanum2.jpg (500x143 - 19 K) metaxytherium_floridanum.jpg (750x215 - 40 K) Based on Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals Skeleton of Metaxytherium floridanum, a Miocene halitheriine dugongid. Total length about 3.2 meters. After Domning (1988); original image, Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. Re-illustrated by Sharon Mooney, 2006. Public Access images may be redistributed, on condition all original credits are kept intact. |

Evolution in Sirenian Locomotion sirenian_locomotion.gif (500x300 - 16 K) Based on Marine Mammals: Evolutionary Biology, Annalisa Berta, James L. Sumich Evolution in Sirenian Locomotion. Re-illustrated by Sharon Mooney, 2006 Public Access images may be redistributed, on condition all original credits are kept intact. |

West Indian Manatee west_indian_manatee.jpg (500x204 - 19 K) Based on Sirenians of the World Re-illustrated by Sharon Mooney, 2006 Public Access images may be redistributed, on condition all original credits are kept intact. |

West African Manatee west_african_manatee.jpg (500x248 - 23 K) Based on Sirenians of the World Re-illustrated by Sharon Mooney, 2006 Public Access images may be redistributed, on condition all original credits are kept intact. |

Steller's Sea Cow stellers_sea_cow.jpg (500x158 - 16 K) Based on Sirenians of the World Re-illustrated by Sharon Mooney, 2006 Public Access images may be redistributed, on condition all original credits are kept intact. |

Dugong dugong.jpg (500x191 - 16 K) Based on Sirenians of the World Re-illustrated by Sharon Mooney, 2006 Public Access images may be redistributed, on condition all original credits are kept intact. |

Amazonian Manatee amazonian_manatee.jpg (500x209 - 17 K) Based on Sirenians of the World Re-illustrated by Sharon Mooney, 2006 Public Access images may be redistributed, on condition all original credits are kept intact. |

Sirenian Evolution Chart (Manatee, Dugong, Sea Cows) sirenians_evolution_graph.gif (500x881 - 46 K) Based on Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals Re-illustrated by Sharon Mooney, 2006 Public Access images may be redistributed, on condition all original credits are kept intact. |

Protosiren Fraasi, 1906, Andrews protosiren_andrews_1906_750.jpg (750x814 - 149 K) protosiren_andrews_1906_500.jpg (500x542 - 73 K) protosiren_andrews_1906.jpg (860x933 - 201 K) Type specimen of Protosiren fraasi Abel as illustrated, 113 natural size, by Andrews (1906) [CGM 101711. Type is a nearly complete cranium shown here in A, ventral view; C, posterior view; and D, dorsal view. B shows worn surface of right I' tusk (crowns of left and right I' tusks are preserved as casts in NHML and UM replicas of the type made at the turn of the century, but they are no longer preserved in the original type). Reconstruction of premaxillary rostrum shown here is too long and straight (plaster reconstruction, now missing in original type, is shown with crosshatching). Andrews (1906) and Abel (1928) interpreted P4 or dp4 as having multiple roots, but Protosiren is now known to have retained both P4 and P' as single-rooted teeth. Based on Cranial Morphology of Protosiren fraasi, (Mammalia, Sirenia) from the Middle Eocene of Egypt: A New Study Using Computed Tomography Public Access images may be redistributed, on condition all original credits are kept intact. |

Protosiren Fraasi from Egypt protosiren_750_nolabels.jpg (750x445 - 52 K) protosiren_750_labels.jpg (750x445 - 61 K) protosiren_750_5_premolar.jpg (750x445 - 56 K) protosiren_500_nolabels.jpg (500x297 - 27 K) protosiren_500_labels.jpg (500x297 - 32 K) protosiren_500_5_premolar.jpg (500x297 - 29 K) New reconstruction of type skull of Protosirenfraasi, CGM 10171, with additions from SMNS 10576. Dentary is shown in outline, based on CGM 42297, which may be part of type specimen (see Andrews, 1906). Reproduced ca. 0.45 x natural size. Abbreviations (after Domning, 1978, with additions): AC, alisphenoid canal; AS, alisphenoid; c', upper canine alveolus; EO, exoccipital; FR, frontal; 1' etc., upper incisor alveoli; J, jugal; MI etc., lower molars; MF, mastoid foramen; MX, maxilla; OC, occipital condyle; P1 etc., upper premolar alveoli; PA, parietal; PM, premaxjlla; SO, supraoccipital; SQ, squamosal; SR, sigmoid ridge. Based on Cranial Morphology of Protosiren fraasi, (Mammalia, Sirenia) from the Middle Eocene of Egypt: A New Study Using Computed Tomography Re-illustrated by Sharon Mooney, 2006 Public Access images may be redistributed, on condition all original credits are kept intact. |

Eotheroides aegyptiacum eotheroides_aegyptiacum_702 (702x988 - 132 K) eotheroides_aegyptiacum_500 (500x704 - 72 K) Type specimen of Eotheroides aegyptiacum (Owen) as illustrated, natural size, by Owen (1875) [specimen is now catalogued as NHML 467221. Type is a natural stone endocast shown here in A, right lateral view; B, dorsal view; and C, ventral view. Abbreviations are as follows: a, "pons Varolii"; b, anterior myelonal columns; c, limit of posterior myelonal columns;f, falx cerebri; o, optic nerve; r, tramverse ridge separating impressions of basisphenoid and basioccipital; p, pedicle of pituitary body; R, rhinencephalon (olfactory bulb); tr, trigeminal nerves; v, upper vermiform process; x, lateral myelonal columns; 5, prominence anterior to sylvian fissure. Illustration and abbreviations reproduced from Owen (1875). Based on Cranial Morphology of Protosiren fraasi, (Mammalia, Sirenia) from the Middle Eocene of Egypt: A New Study Using Computed Tomography Public Access images may be redistributed, on condition all original credits are kept intact. |

Cranium of Protosiren fraasi protosiren_cranium_750.jpg (735x1024 - 106 K) protosiren_cranium_500.jpg (500x696 - 63 K) Cranium of Protosiren fraasi, A Dorsal, B left lateral, C palatal views Priem referred his dentary to the same taxon as Andrews' CGM 42297, possibly anticipating that it would look like CGM 42297 when fully adult. Then Priem, citing Abel (1904, 1906), called Andrews' specimen, and hence his own, Protosirenfrmi. Later Sickenberg (1934) considered Priem's dentary "probable" to represent P. fraasi and referred no other dentaries to this species (inexplicably ignoring CGM 42297). Thus small dentaries with very narrow symphyses have come to typify Protosiren (compare Domning et al., 1982, figs. 20, 21, and 34). However, specimens collected in Wadi Hitan (Zeuglodon Valley) in Egypt in recent years show that Protosiren there has a large dentary with large molars, and a wide mandibular rostrum with well-spaced alveoli for all anterior teeth Domning and Gingerich, 1994), while Eotheroides has the smaller dentary with smaller molars and a narrower rostrum (like Priem's dentary). Andrews was correct to place CGM 42297 in the same taxon as CGM 10171, and it might even be part of the type specimen (fide Andrews, 1906, p. 210). Both represent Protosiren fraasi. Based on Cranial Morphology of Protosiren fraasi, (Mammalia, Sirenia) from the Middle Eocene of Egypt: A New Study Using Computed Tomography Public Access images may be redistributed, on condition all original credits are kept intact. |

No comments:

Post a Comment