The National Geographic Magazine, May 1911

SHORE WHALING: A WORLD INDUSTRY

By Roy Chapman Andrews

Assistant Curator of Mammals, American Museum of Natural History

With Photographs by the Author

IF THE European and American people could be educated to the point of eating the canned flesh of animals which individually yield as much as 80,000 pounds of meat, what a wonderful food supply would be within reach of the poor in our great cities! In Japan this has actually been accomplished and hundreds of tons of whale flesh are sold in the markets of all the large towns and villages to people who would otherwise have little variety to their diet of rice and fish.

This great meat supply has been put into their hands indirectly by a Norwegian, for it was not until 1864, when Swend Foyn invented the harpoon-gun, that whales could be taken in such a manner as to allow any parts except the oil and baleen (the "whalebone" of commerce) to be utilized.

With the further development of the harpoon-gun grew up a new and great industry, for it made possible the capture of a group of whales known as rorquals, or "finners," in sufficient numbers to warrant the erection of stations at certain points on the shore where the animals could be brought in and the huge carcasses converted into commercial products. Previously these whales had been little troubled by the men who hunted in a small boat with a hand harpoon and land, for the great speed of the animals and their tendency to sink as soon as killed, as well as their thin blubber and short, coarse baleen, made them unpopular with the early whalers.

In a few years stations had sprung up on the coasts of Norway in every available plant, and later reached across the Atlantic to the American shores. Newfoundland became the first hunting grounds for the whalers here, and only a few years ago as many as 18 stations were in operation on that island and the immediate vicinity.

The great success of the Norwegian methods attracted so much attention that stations were erected in every part of the world where conditions were favorable-in British Columbia, southeastern Alaska, Bermuda, South America, and the islands of the Antarctic; on the coasts of Japan, Korea, Africa and Russia. Australia is soon to be invaded, and only a few months ago a company announced their plans for carrying on operations on a large scale in the Aleutian Islands. In New Zealand, humpback whales are being taken in wire nets, and so in nearly every part of the globe the world-hunt goes on.

And what is to be the result of this wholesale slaughter? Inevitably the commercial extinction of the large whales, and that within a very few decades. In some localities this has already taken place and all the whales have been killed or driven from their feeding grounds.

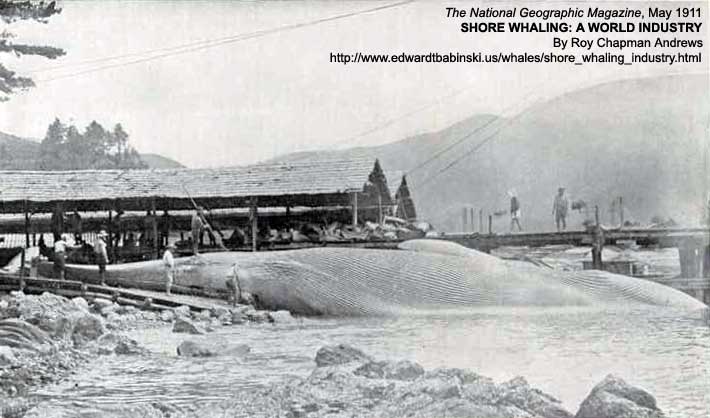

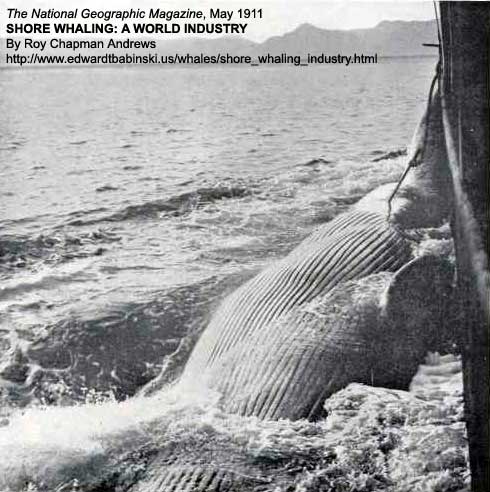

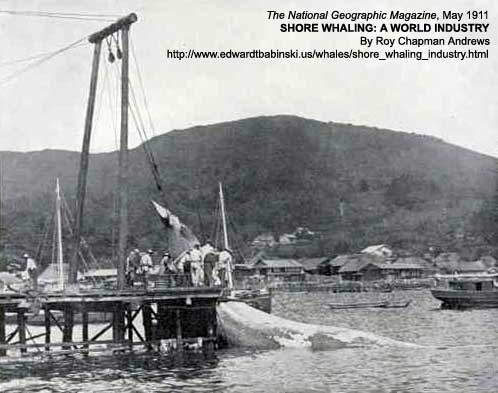

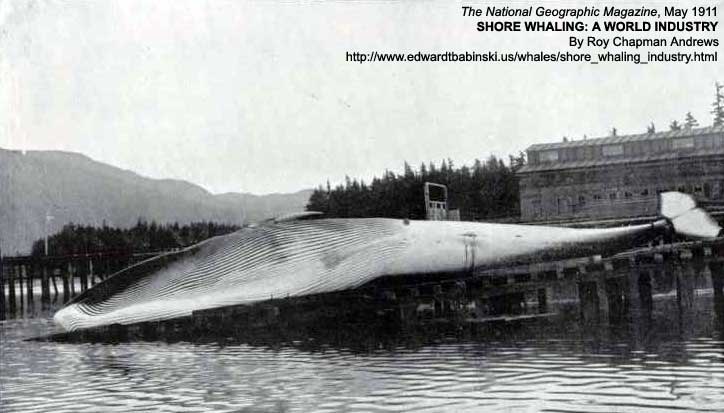

A Big Blue or Sulphur-Bottom Whale: Japan

"The blue or sulphur-bottom whale found in all our oceans is not only the largest animal that lives today, but is also, so far as is now known, the largest animal that has ever existed on the earth or in its waters. I have heard many stories of the almost incredible way in which these animals can pull, but was at first inclined to doubt them. Later, when I saw a blue whale with a harpoon between the shoulders drag the ship, with engines at full speed astern, through the water almost as though it had been a rowboat, I began to listen with more respect" (see page 427)

Photo by Roy Chapman Andrews

This method of capture has, however, made possible a careful study by naturalists of most of the species of large whales and their habits, besides enabling museums to secure skeletons and other specimen for exhibition. Thus, when the American Museum of Natural History in New York city began to gather such material, it led to a series of expeditions which carried the writer to a number of stations in widely separated parts of the world.

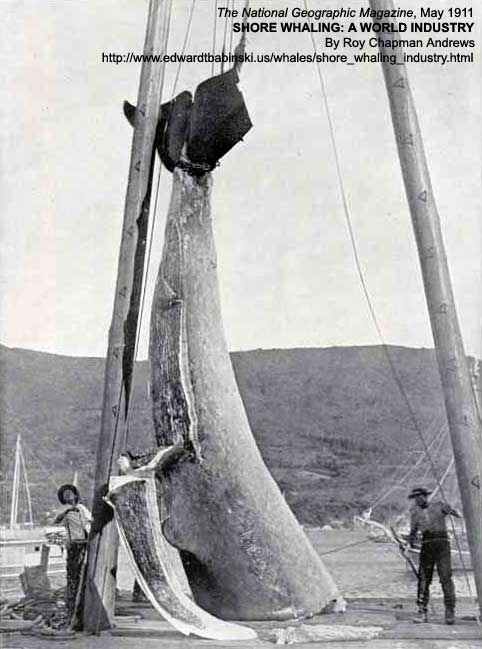

THE ENORMOUS BODIES EASILY HANDLED

I will never forget my intense surprise at the extraordinary ease and quickness with which the enormous carcasses are handled when I first saw a whale "cut in." It was at Sechart, in Barclay Sound, on the west coast of Vancouver Island. Here, as at all of the American stations, the operations are carried on in the Norwegian way.

The ship had arrived at 1:30 a.m. with three humpbacks, which were left floating in the water, tied to the end of the wharf, near a long inclined platform called the "slip." Work began at seven o' clock, and, as I had only just been awakened, I ran out without waiting for breakfast, thinking that there would be ample time to eat when the operations were under way. I soon learned, however, that there were no "breathing spells" when whales were being cut in, and every soul was at his work until the whistle blew for dinner at noon.

A heavy wire cable was made fast about the posterior part of one of the whales just in front of the tail, or "flukes," and the winch started. The cable straightened out, tightened, and became as rigid as a bar of steel. Slowly foot after foot of the wire was wound in and the enormous carcass, weighing perhaps 45 tons, was drawn out of the water upon the slip.

One of the Japanese (for men of six nationalities--Chinese, Japanese, Norwegians, Newfoundlanders, Indians, and Americans--are employed at these west-coast stations) scrambled up the whale's side, and balancing himself on the smooth surface by the aid of his long knife, made his way forward to sever at the "elbow" the great side fin, or flipper, 16 feet in length.

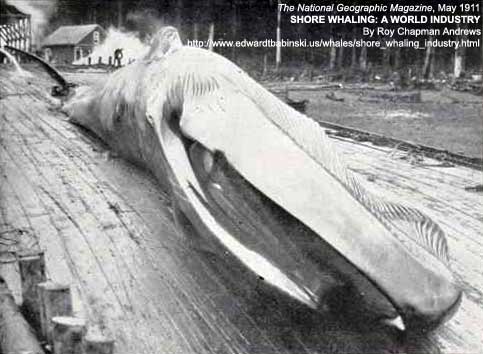

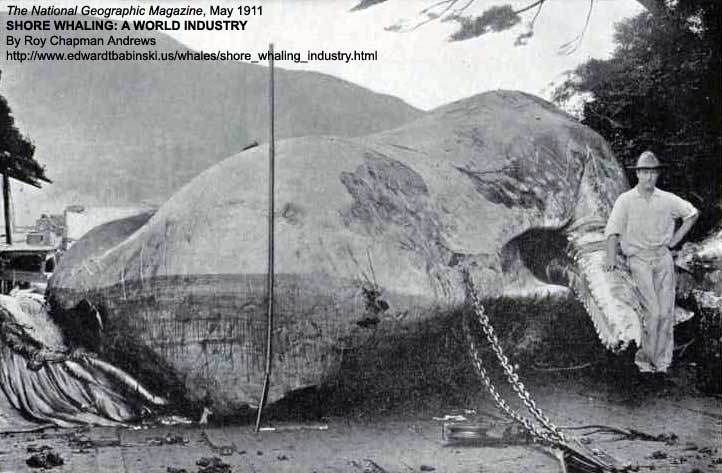

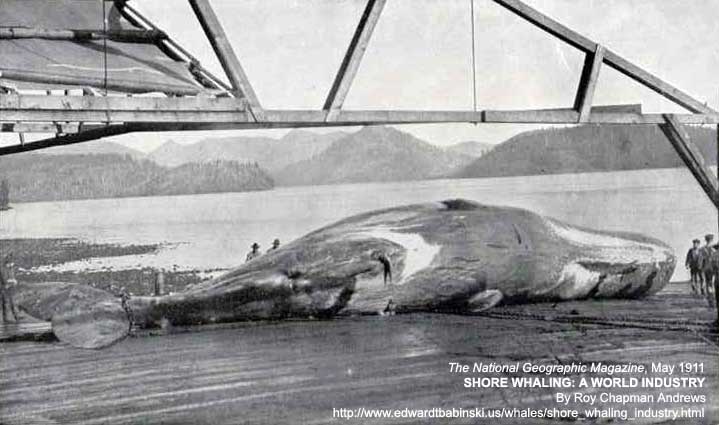

A Blue Whale: Vancouver

Although the mouth is enormous, large enough in fact to permit 10 or 12 men to stand upright in it, the throat measures only about 9 inches in diameter (see page 427)

Photo by Roy Chapman Andrews

A Blue Whale: Vancouver

Specimens of this whale have been measured which reached a length of 87 feet, and, in all probability, weighed as much as 75 tons (see page 427)

Photo by Roy Chapman Andrews

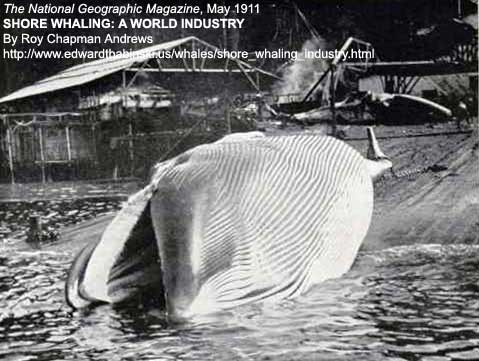

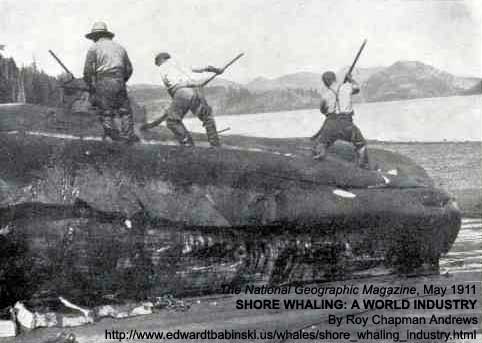

THE WHALES ARE PEELED LIKE AN ORANGE

Before the carcass was half out of the water other cutters, or "flensers," as they are called, had begun to make longitudinal incisions through the blubber along the breast, side, and back, and from the flukes the entire length of the body to the head. The cable was then made fast to the blubber at the chin, the winch started, and the great layer of fat stripped off exactly as one would peel an orange. When the upper side had been denuded of its blubber covering, the whale was turned over by means of the "canting winch" and the other surface flensed in the same manner.

A Finback Whale: Vancouver

Photo by Roy Chapman Andrews

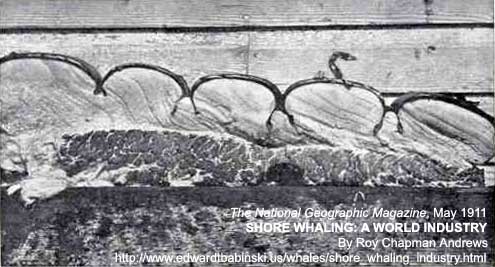

The blubber is a layer of fat of varying thickness which covers the entire body of all whales, porpoises, and dolphins and keeps the animal warm. It acts exactly as the feathers of birds or the hair of land mammals--as a non-conductor to prevent the natural heat of the body from being absorbed by the water in the one case, and the air in the other. On the great bowhead, or Greenland right whale, which lives in the intensely cold waters of the Arctic Ocean, the blubber is 12 or 14 inches thick in some places.

When the "blanket pieces," as the blubber strips are called, were torn from the carcass, they were cut into large oblong blocks and fed into a slicing machine, chipped to small bits, carried upward and dumped into enormous vats, to be boiled or "tried out" for oil.

The carcass had meanwhile been split open by chopping through the ribs of the upper side, a heavy hook was attached to the tongue bones at the throat, and the entire mass of heart, lungs, live, and intestines drawn out at once. The body was then hauled to the "carcass platform," at right angles to the "flensing slip," the flesh torn from the bones by the aid of the winch, and the skeleton disarticulated.

Both flesh and bones were piled separately into great open vats which bordered the carcass platform, and boiled to extract the oil. The flesh was then artificially dried and sifted, thus being converted into a very fine guano, and the bones pulverized to form "bone meal," also a fertilizer. Even the blood, of which there are several tons in a large whale, was carefully drained from the slip into troughs, boiled, dried, and made into guano. Finally, the water in which the blubber had been tried out was converted into glue.

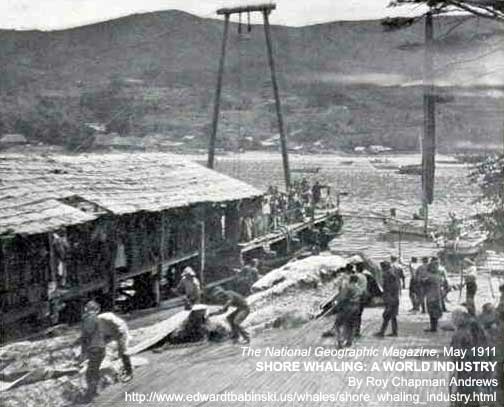

The Carcasses of Five Humpback Whales: Vancouver

This whale is considerably smaller than the blue whale, its maximum size being 55 feet.

Photo courtesy of World's Work

The baleen, or whalebone, which alone remained to be disposed of, was thrown aside, to be cleaned and dried as opportunity offered. The baleen of all the rorquals is short, coarse, and stiff, and in Europe and America has but little value. In Japan, however, it is made into many useful and beautiful things.

This, with the exception of minor details, is the method of handling whales which the Norwegians developed after years of experimenting, and which is followed in almost all other parts of the globe except Japan.

A very white Humpback Whale, Vancouver: Note the Crab-like Flipper

"It's body is thick and heavy, with enormous side fins, or flippers. These great paddles are one-quarter the length of the entire body, and a single one from a whale 49 feet long weighed on the station scales 956 pounds."

Photo by Roy Chapman Andrews

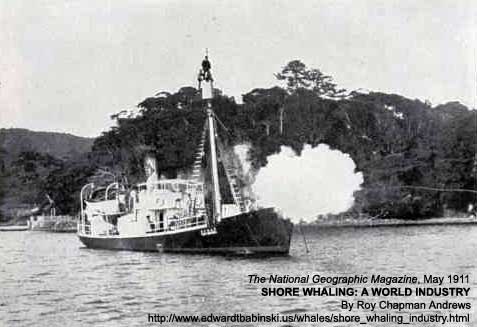

A Modern Whaler In Port

The crew are practicing by shooting at a floating target.

Photo by Roy Chapman Andrews

The Japanese Whale Fisheries

In the Island Empire shore-whaling as a great industry has developed during the last 15 years, but nowhere else in the world are the by-products so perfectly utilized. The Japanese have not only extracted the best from the European methods of preparing whales and adapted it to their peculiar needs, but have also added much from their own experience which whalemen of other nations would do well to recognize.

The Japanese stations are usually situated in or near one of the little fishing villages which dot the islands in every bay or harbor. In some instances the whales are drawn out of the water upon a slip in the manner learned from the Norwegians, but the more usual way of cutting in is a method of their own adoption.

At the end of a wharf extending into deep water a pair of long, heavy poles are erected, inclined forward, and joined at their extremities by a massive cross-piece. From this the great blocks, through which run the wire cables of the winch, are suspended.

The first whale which I saw cut in by the Japanese was an enormous sulphur-bottom, 80 feet in length. I had been at sea for several days on one of the ships, and as we swung into the bay from the open ocean, the whistle echoing among the hills gave warning of our coming. The little vessel, towing a carcass almost as long as herself, plows slowly up to the wharf, and after a rope from the shore had been made fast to the flukes of the whale, dropped it into the water and backed off to anchor in the bay.

Immediately a heavy chain, was made fast about the body just forward of the tail, the winch started, and the whale drawn slowly into the air over the end of the wharf. As it came upward the eager cutters attacked it, slicing off enormous blocks of flesh and blubber, which were at once seized by "hookmen" and drawn to the back of the platform. Meanwhile two other cutters were at work in a "sampan" dividing the carcass just forward of the dorsal fin. The entire posterior part of the whale was then drawn upward and lowered on the wharf to be stripped of blubber and flesh. Transverse incisions were made in the portion of the body remaining in the water, a hook fastened to a blanket piece, and as the blubber was torn off by the winch the carcass rolled over and over. The disjointed head was hoisted bodily onto the pier. Section by section the carcass was cut apart and drawn upward to fall into the hands of men on the wharf and be slicked into great blocks two or three feed square.

The scene was one of "orderly confusion"--men, women, and girls laughing and chattering, running here and there, sometimes stopping for a few words of banter, but each with his, or her, own work to do. Above the babel of sounds, the strange, half-wild, meaningless chant, "Ya-rå-cü-ra-sa," rose and died away, swelling again in a fierce chorus as the sweating, half-naked men pulled and strained at a great jawbone or swung the hundred-pound chunks of flesh into the waiting hand-cars which carried them to the washing vats. Sometimes a kimona-clad, bare-footed girl slipped on the oily boards or treacherous, sliding, blubber cakes and sprawled into a great pool of blood, rising amid roars of laughter to shake herself, wipe the red blotches from her little stub nose, and go on as merrily as before.

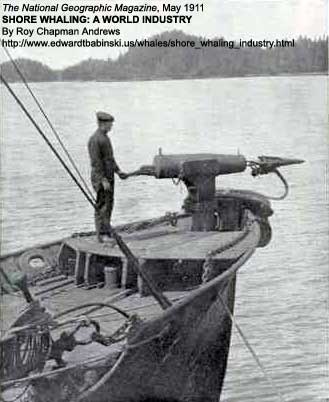

The Harpoon Gun used for killing and capturing whales

Photo courtesy of World's Work

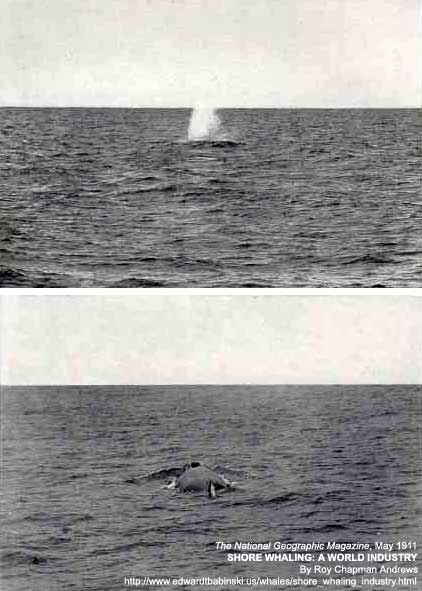

A Sei or Sardine Whale Spouting: Japan

A Sei or Sardine Whale Inspiring

Photo by Roy Chapman Andrews

It was essentially a good-natured crowd, working hard and ceaselessly, but deriving as much fun from their labor as though it was a holiday. The spirit of the place was infectious, and as I splashed about in the blood and grease doing my own work, I talked and joked with the cutters in bad Japanese, causing screams of laughter when I seriously informed them that "the sun was very hot water" by the quite natural mistake of substituting the word "atsui-yu" for "atsui" (hot).

Almost every night we would be awakened by the long-drawn wail of a ship's sire whistle, bringing the news of more whales. If I did not at once stir, the little amah (servant), always devoted to my interests, would quietly slide back and paper screen to the sleeping-room and say "Andrews-sar Go Hogei wa kujira torri mashita" (Hogei, No. 5 caught whales). When I had rolled out of the comfortable futons and begun to dress, I would hear little Scio-san pattering about in the other room, gathering my pencil, note-book, and tape measure. Looking like a beautiful night-moth in her bright-colored kimono, with the huge bow of her obi (sash) always neatly arranged; she would be there to help me into the greasy oil-skins and rubber boots, and clump along in front to the wharf, lighting the way with a "chôchin" (paper lantern) that I might not bump my head on the eaves and rafters of the low station sheds.

A Finback Whale Diving: Japan

This species derives its name from the large fin on its back, and which is clearly shown in this picture.

Photo by Roy Chapman Andrews

Sei Whale about to take a "surface dive"

This species may be easily recognized in the water by the height of the dorsal fin. "It is most interesting to watch these beautiful animals pursuing a school of sardines, twisting their lithe bodies as they whirl along after the terrified, skipping fish, sometimes throwing themselves half out of the water in their eagerness. But, like the other finners, they will always eat shrimp, if it is obtainable, in preference to anything else."

Photo by Roy Chapman Andrews

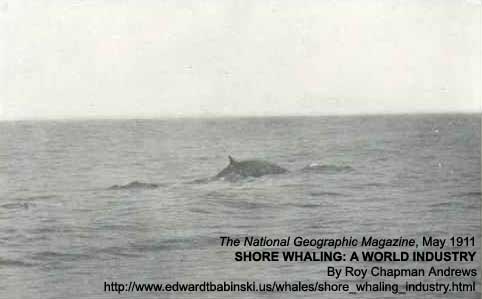

Humpbacks often swim in pairs while feeding

Photo courtesy of World's Work

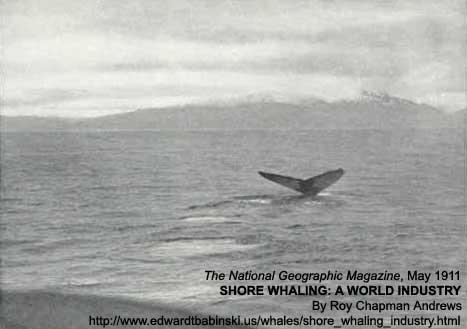

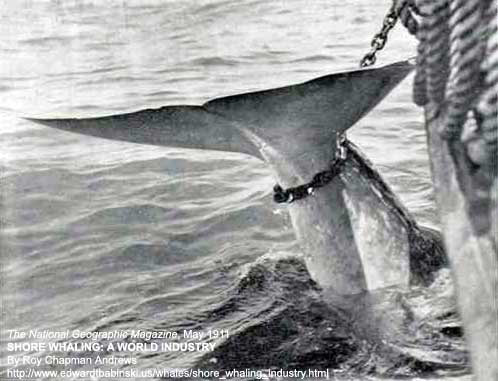

The flukes of a big humpback just disappearing beneath the surface.

The smooth spot, or "slick" on the water is the invariable accompaniment of the dive.

Photo courtesy of World's Work

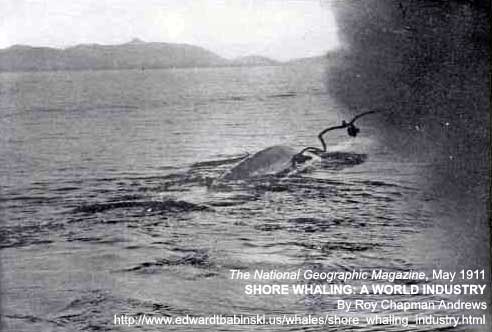

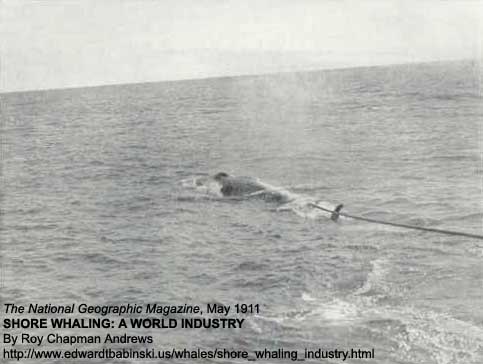

The Harpoon as it strikes the whale

In addition to the rope, the harpoon carries a bomb, which is exploded three or four feet inside the whale and usually kills the huge animal instantly. The black cloud is the smoke from the discharge.

Photo by Roy Chapman Andrews

Every day Scio-san religiously went to her ugly little stone joss in the playhouse temple on the hillside and prayed that the "America-san" might catch many whales and porpoises for the hakubutsu-kwan (museum) in the wonderful, fairy city across the Pacific, of which he had so often told her. And when the season was ended and she had ventured to ask the America-san t himself thank the joss, and to please her he had done so, her joy could hardly be contained, and the tip of her little nose was almost red from constant rubbing on the tatami (floor matting) in her bows of thanks and farewell.

Even though it was the very middle of the night when a ship's whistle sounded, long before the whale had been dropped at the wharf paper lanterns, flashing like fireflies, would begin to shine and disappear among the thatched-roofed cottages and a crowd of villagers gather at the end of the wharf. Half-naked men, child-faced geishas, and little youngsters carrying sleeping babies as large as themselves strapped to their backs, formed a curious, picturesque, ever-changing group.

Inflating the carcass of a humpback whale to keep it afloat

A hollow steel tube is thrust into the whale's side and the animal is slowly filled with air by a steam pump.

Photo courtesy of World's Work.

Towing the inflated whale to the factory.

Photo by Roy Chapman Andrews

Fires of coal-fat in iron racks along the wharf threw a brilliant yellow light far out over the bay filled with whale ships, heavy, square-sterned fishing boats, and sampans. The work of cutting in would go on as merrily as in the daytime, for the meat and blubber must be hurried on board fast transports and sent to the nearest city, to be sold in the markets and peddled from house to house.

WHALE MEAT IS VERY POPULAR IN JAPAN

Few people realize the great part which whale meat plays in the life of the ordinary Japanese. Too poor to buy beef, their diet would include little but rice, fish, and vegetables were it not for the great supply of flesh and blubber furnished by these huge water mammals. In winter the meat of the humpback whale, which is most highly esteemed, sometimes brings as much as 30 sen (15 cents) per pound; but this is unusual. Ordinarily it can be bought for 15 sen or less. But the edible portions are not only the flesh and blubber. Certain parts of the viscera are prepared for human consumption, and what remains is first tried out to extract the oil, then chipped by girls using hand-knives, and dried in the sun for fertilizer.

Whale meat is very coarse grained and tastes something like venison, but has flavor peculiarly its own. I have eaten it for many days in succession, and found it not only palatable but healthful. The Japanese prepare it in a variety of ways, but perhaps it is most frequently chopped finely, mixed with vegetables, and eaten raw, dressed with a brown sauce.

The Flensers at work on a Sperm Whale's Head: Vancouver

"They make longitudinal incisions through the blubber along the breast, side and back, and from the flukes the entire length of the body to the head. The cable was then made fast to the blubber at the chin, the winch started, and the great layer of fat stripped off exactly as one would peel an orange."

Photo by Roy Chapman Andrews

In the summer, when it is impossible to ship the meat to any distance because of the heat, much of it is canned. The flesh is cooked in great kettles, and the cans made, packed, and labeled at the stations. On my desk as I write is a tin of whale meat which I bought from Aikawa, where hundreds of pounds were packed and sent southward to be marketed at Tokyo and shipped to all parts of the Empire.

It is most unfortunate that prejudice prevents whale meat from being sold in Europe and America. It could not, of course, be sent fresh to the large cities; but, canned in the Japanese fashion, it is vastly superior to much of the beef and other tinned foods now on sale in our markets. In New Zealand the Messrs. Cook Brothers, who have developed a most extraordinary method of capturing humpback whales in wire nets, can a great deal of meat and ship it to the South Sea Islands, where it is sold to the natives.

The baleen of the rorquals, which is of little value in Europe and America, has been put to many uses by the Japanese. When I visited the exhibition rooms of the Toyo Hogei Kaisha, in Tokyo, I was astonished and delighted at sight of the cigar and cigarette cases, charcoal baskets, sandals, and other beautiful things created by their clever brains and skillful fingers from the material which, in the hands of western nations, seems to be useless.

Cross-section of blubber on breast of whale, showing the folds

Photo by Roy Chapman Andrews

The whales are going fast, and it is probable that long before the slow-moving wheels of government begin to revolve and legislation is enacted for their protection, they will have become commercially extinct. But since this seems to be unavoidable, my hopes are that the Japanese will get even more than their share while they do last. There the whales are as carefully prepared and utilized for as great a purpose as are cattle and sheep in the Occident. In other countries but little of the real value of the animals is secured, and their great bodies are being spread upon the southern cotton fields instead of feeding thousands of hungry poor.

THE BLUE WHALE

I have been writing of the methods of preparing whales, but have told little of the animals themselves. Few readers, perhaps, realize that the blue or sulphur-bottom whale found in all our oceans is not only the largest animal that lives today, but is also, so far as is now known, the largest animal that has ever existed on the earth or in its waters. Specimens have been measured which reached a length of 87 feet and in all probability weighed as much as 75 tons. Although the mouth is enormous, large enough in fact to permit 10 or 12 men to stand upright in it, the throat measures only about 9 inches in diameter.

These animals, like most of the "whale-bone whales," usually feed on minute crustaceans, a shrimp about three-quarters of an inch long. They probably never eat fish of any kind if other food is to be had, and of the many stomachs which I have examined, never once could anything but the little red crustaceans be found. From the stomach of one blue whale at Vancouver Island five barrels (1,215 pounds) of shrimp were taken, and it was by no means full.

The Norwegians gave the animal the name of blue whale from the bluish cast to the beautiful gray body. Sulphur-bottom, as the whale is called at the American station, is a misnomer and unfortunate, for there is not the slightest trace of yellowish color anywhere upon the animal.

Making a whale fast to the side of the ship: Japan

Photo by Roy Chapman Andrews

Probably no Cetacean has such wonderful strength as have the blue whales. I have heard many stories of the almost incredible way in which these animals can pull, but was at first inclined to doubt them. Later, when I saw a blue whale with a harpoon between the shoulders drag the ship, with engines at full speed astern, through the water almost as though it had been a rowboat, I began to listen with more respect. Since the tail is used almost exclusively for propelling the animal forward, if the iron strikes far back the whale is greatly hampered in its swimming movements; but with the harpoon between its shoulders it can pull with all its strength.

THE FINBACK, OR "GREYHOUND OF THE SEA"

The finback, closely related to the blue whale, has been called the "greyhound of the sea," for its long, slender body is built on the lines of a racing yacht and the animal can equal the speed of the fastest steamship. The back is dark gray, shading into beautiful light gray on the sides and pure white below. A noticeable character about this whale is the asymmetry of the throat coloring; the left side is dark slate and the right pure white like the under parts. The baleen, also, on the right side, for a distance of about 2½ feet, is white, in sharp distinction from the remaining dark places.

THE HUMPBACK IS VERY PLAYFUL

The humpback is to me the most interesting of all our large whales, partly because of the fact that its habits are more easily studied than are those of the other members of the family. Its maximum size is under 55 feet, but its body is thick and heavy, with enormous side fins, or flippers. These great paddles are one-quarter the length of the entire body and a single one from a whale 49 feet long weighed on the station scales 956 pounds. The throat, breast, flukes, and flippers of the humpback are almost invariably covered with masses of barnacles, for the hard, shell-like Coronula are themselves the hosts of the soft, pendant goose barnacles.

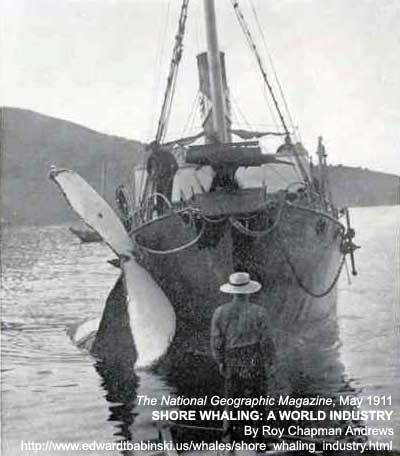

Bringing In A Humpback: Japan

This is not a propeller, but the whale's tail.

Photo by Roy Chapman Andrews

Barnacles are not the only parasites which infest these animals, for the humpbacks, and in fact almost all the large whales, bear numbers of crab-like crustaceans (Cyamus), about half and inch in length, called "whale lice." On the right whales these "lice" produce an irritation upon the top of the snout that a large, irregular roughened patch, called the "bonnet," is formed: on the side of the lip and over the eyes are other and smaller patches infested with the troublesome crustaceans.

The most playful of all our large whales are the humpbacks, and consequently that are the most interesting to the photographer. Jumping or "breaching" is one of their most spectacular performances, and it is truly a wonderful sight. The first time I ever saw a humpback "breach" was off the Vancouver Island coast while on board the ship Orion. We had sighted a lone bull whale late in the afternoon, and for two hours the little ship had been hanging doggedly to the chase.

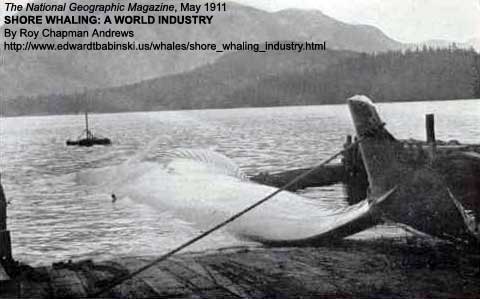

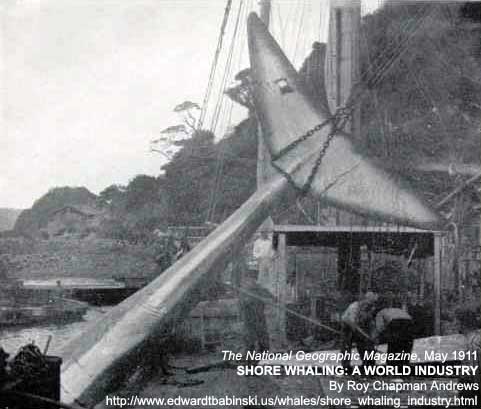

Drawing a Finback up on the ways to be cut up: Japan

Photo by Roy Chapman Andrews

The whale seemed to know exactly the number of fathoms at which the harpoon gun was effective and gauged the distance accurately, always coming up just out of range. Sometimes the animal thrust its entire head and fore part of the body out of the water, with a loud, whistling spout, sinking back out of sight before the ship could swing about. Again, it inverted itself and, with the entire posterior part out of the water, began to wave the gigantic flukes back and forth. The motion was slow and dignified at first, the flukes not touching the water on either side. Faster and faster they waved, until they were lashing the water into foam and sending clouds of spray high into the air; then slowly the action ceased and the whale sank out of sight. The ship was not far from the animal as it went down and I stood waiting on the gun platform, when suddenly the water parted directly in front of us and with a rush that sent its huge, black body five feet clear of the surface the whale shot into the air, fins extended, and fell back on its side, sinking slowly out of sight amid a perfect cloud of spray.

Stripping the flesh from the skeleton of a Giant Finback Whale: Japan

Photo by Roy Chapman Andrews

THE SEI, OR SARDINE WHALE

While in Japan during 1910 I had an opportunity to study in considerable detail a species which has never before been reported in numbers from the North Pacific. This is the sei whale of the Norwegians and the "Iwashi kujira" (sardine whale) of the Japanese. It is not a large animal, seldom exceeding 54 feet, and is formed on slender, graceful lines, much like the finback. Its coloration also resembles in a general way the latter species, but it can be readily distinguished by its high, falcate dorsal fin.

The sei whale has a habit of swimming just below the surface, sometimes with the dorsal fin exposed, and when feeding will travel for a considerable distance in this manner. It is a difficult whale to shoot, because the back is arched but slightly when the animal dives and only a comparatively small part of its body is shown above the water at one time. I have seen a sardine whale, rising almost under the bows of a ship, suddenly check its upward rush and dash along just below the surface, the vessel going at full speed beside it in order to spout.

It is most interesting to watch these beautiful animals pursuing a school of sardines, twisting their lithe bodies as they whirl along after the terrified, skipping fish, sometimes throwing themselves half out of the water in their eagerness. But, like the other finners, they will always eat shrimp, if it is obtainable, in preference to anything else.

Lifting a Giant Finback Whale out of the water so that the cutters can get at it

Photo by Roy Chapman Andrews

WHALES ARE DEVOTED TO THEIR CALVES

All the large whales show great affection for their young, and the cows and calves will seldom leave each other when pursued by a ship. I remember at one time in Alaska, on board the steamship Tyce, Jr., we had sighted a female finback with a young one about 30 feet long beside her. They were not difficult to approach, and as the old whale rose to spout not five fathoms from the vessel's nose, the gunner fired, killing her almost instantly. The calf, although badly frightened, continued to swim in a circle about the ship, and finally, when its dead mother had been hoisted to the surface, the little fellow came alongside so close that I could have struck him with a stone. During the time that the carcass was being inflated and the gun reloaded, the calf was constantly within a few fathoms of the ship, swimming around and around, sometimes rubbing itself against the body of its dead mother. Finally a harpoon was sent crashing into its side, and it sank without a struggle.

Hoisting on the wharf parts of the whale shown in the preceding picture

Photo by Roy Chapman Andrews

PECULIARITIES OF WHALES

The feeding operations of the humpback, blue, and finback whales are carried on in essentially the same way and are most interesting to watch. If the "feed" happens to be floating at the surface, as is frequently the case in the morning and evening, the action can be easily seen. The whale opens its mouth, takes in a great quantity of water containing numbers of the floating shrimp, turns on its side, and brings the ponderous lower jaw upward, closing the mouth. The great, flexible tongue, filling the space between the rows of baleen, forces out the water, leaving the little shrimp, which have been strained out by the bristles on the inner side of the whalebone plates. The fin and one lobe of the flukes are thrust into the air as the mouth is closed, and sometimes the animal rolls from side to side. At this time the whales are careless of danger and pay not the slightest attention to the ship which is hunting them.

The distance traversed by whales when beneath the surface depends entirely upon circumstances. When there is little feed and the animals are constantly moving or "traveling," they may rise to spout several miles from the place of last appearance. If, on the contrary, feed is abundant, they may blow again within a short distance of the point at which they disappeared, and continue for several hours within two or three miles of the same spot.

Head of the 60-foot Sperm whale sent to the American Museum in New York: This head yielded 20 barrels of spermaceti

Photo by Roy Chapman Andrews

Posterior part of a sei or sardine whale drawn upon the wharf: Japan

This picture shows very distinctly the layer of blubber, or fat, which covers the entire body of all whales -- the white layer enveloping the dark flesh.

Photo by Roy Chapman Andrews

A big bull sperm whale: Vancouver Island

"The sperm whale is the animal which yields ambergris, the valuable substance used so extensively in the manufacture of our best perfumes. Ambergris is only found in 'sick' whales; that is, its presence is not normal, but is caused by a pathological condition of the intestines." Contrast the huge head and bulky frame of this species with the "racing build" of the finback whale in the next picture.

Photo by Roy Chapman Andrews

The Greyhound of the Sea: A Female Finback Whale: Alaska

"The finback, closely related to the blue whale, has been called the 'greyhound of the sea,' for its long, slender body is built on the lines of a racing yacht and the animal can equal the speed of the fastest steamship"

Little is known about the breeding habits of whales, except that the young of whales are born alive, and are suckled and vigorously defended by the mother, as in the case of land mammals.

Photo by Roy Chapman Andrews

Cross-Section of the Head of a Sperm Whale

This species of whale carries two rows of 20 or 25 heavy teeth in its lower jaw. The teeth may be observed in the left portion of this picture. The teeth assist in holding the giant squid and cuttlefish, on which the enormous animal feeds. This picture also shows very clearly the layer of blubber surrounding the flesh.

Photo by Roy Chapman Andrews

Skull of a Blue Whale sent to the American Museum of Natural History from Japan

Photo by Roy Chapman Andrews

There is a belief current among fishermen that whales can remain under water for a very long time without coming to the surface. This owes its origin to the fact that whales will suddenly appear when for hours before there had been no sign of a spout, even at a distance. I believe this idea may be accounted for by the hypothesis that the animals frequently swim great distances at considerable speed without appearing to blow. The longest period of submergence for finbacks which I actually timed by my watch was 23 minutes, but there is little doubt but that most large whales can remain under water a considerably longer time.

Both humpbacks and finbacks, when two or more individuals are together, will frequently swim side by side so closely as to almost touch each other, leaving the surface and reappearing again at exactly the same instant. Also a school, when separated by perhaps many hundred yards, will disappear as though at a given signal, double under water, and rise again a mile away, all blowing at the same time. How they communicate with each other--for it seems that they must do it--is a mystery for which I cannot even suggest an explanation.

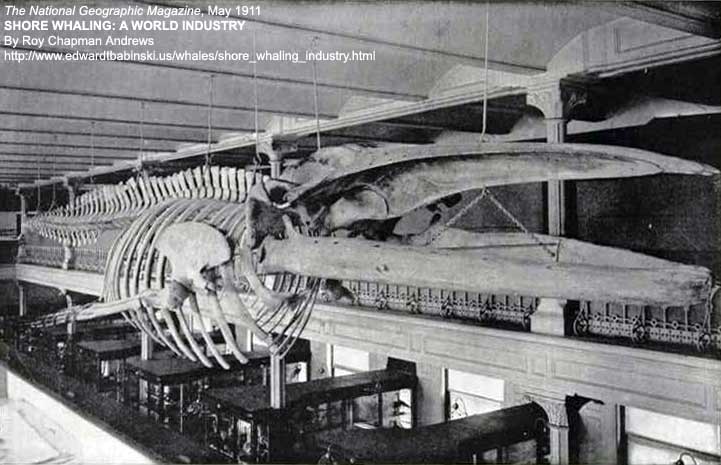

Skeleton of Finback Whale, mounted in the American Museum of Natural History

Photo by Roy Chapman Andrews

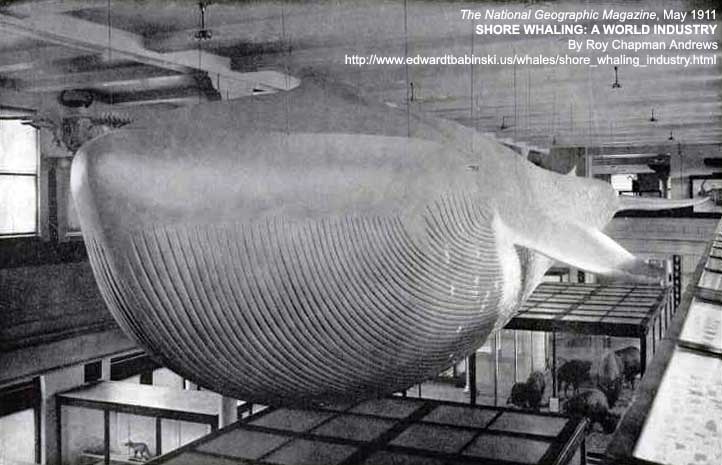

Blue or Sulphur-Bottom Whale: life-size model; Length, 76 feet

In the American Museum of Natural History; prepared under the direction of Roy C. Andrews and James L. Clark

Photo by Roy Chapman Andrews

Whale meat ready to be shipped to the markets: Japan

In Japan hundreds of tons of whale meat are sold in the markets of all the large towns to people too poor to buy beef. The usual price is 7 or 8 cents per pound. One whale yields as much meat as a herd of 100 cattle.

Photo by Roy Chapman Andrews

THE GIANT SPERM WHALE

No mammal which inhabits the sea is more extraordinary and grotesque in appearance than is the heavy-bodied, square-nosed sperm whale, and I suppose no mammal could furnish a more interesting study to the naturalist. At very few of the shore stations are sperms taken, but in the north of Japan, during August and September, they are killed in numbers.

Instead of having plates of baleen, this whale carries a row of 20 to 25 heavy teeth on each side of the lower jaw. These fit into sockets in the roof of the mouth and assist in holding the giant squid and cuttle-fish on which the enormous animal feeds. Since the squid seldom gets far out of the warm currents, the sperm does not go into the cold water, but cruises about in the tropics and in the Gulf and Japan streams.

In the upper portion of the head the whale has an immense oil-tank in which the valuable "spermaceti" is found in a liquid condition and from which it may be dipped out with a bucket when an incision has been made. From a sperm whale 60 feet in length which was sent to the Museum from Japan, 20 barrels of spermaceti were taken out of the "case" and surrounding fat. This oil congeals as soon as it is cooled by the air, but the natural heat of the body keeps it in a liquid condition until the case is opened.

The sperm whale is the animal which yields ambergris, the valuable substance used so extensively in the manufacture of our best perfumes. Ambergris is only found in "sick" whales; that is, its presence is not normal, but is caused by a pathological condition of the intestines. It has been found floating upon the water, and is also taken from the intestines themselves after the whale has died or has been killed. It is used as a vehicle for perfumes and not as an odor itself.

No comments:

Post a Comment